Its 4pm on a day towards the end of June, 2022. I’m leaving Aberdeen, bound up the coast for Fraserburgh. The A90 whips by as an engine warning light comes on the dashboard. In about a week’s time I’ll pay a man in Campbeltown £40 to turn it off but for now it just a source of mystery and anxiety. I’ve already hit Colliestone and Boddam today, quiet sleepy places ringed by a peaceful sea and the industrial fishing fleet of Peterhead respectively, and Fraserburgh represents the third and final site of the day before I find somewhere to wild camp near Gamrie bay. The dog snoozes in the back of the car, quite unaware that he won’t be back in his bed in the corner of my living room for the next two weeks. For him, the next two weeks consists of car rides, mooching on beaches while I stare at rock pools, and curling up at the end of my tiny pop-up tent at spots picturesque and …. suspicious around the coast of Scotland. For me, the next 14 days represented a journey into the unknown, my first serious attempt to collect field data on the beadlet anemone (Actinia equina). This wee gelatinous beastie is found all-round the North Atlantic coast, and within its quivering jelly-like form lies great potential to find answers to interesting sciencey questions. The current project, and the reason I’m sort-of doing the North Coast 500 in my Subaru Forester with a dog in the back and my canoe polo boat on the roof, aims to determine whether long-term chronic exposure to hydrocarbon pollution has caused evolution in anemone populations. There is all sort of oil infrastructure around the coast of Scotland, from ports and pipelines to depots and “remediation sites”, which potentially could be exposing local populations of wildlife to small but persistent levels of pollution over the years. Given the toxicity of these hydrocarbons, we would expect exposed populations to show evolved changes in physiology, behaviour, life-history, or other traits to allow the organisms living there to cope with persistent contact with hydrocarbons. But whether they actually do or not simply isn’t known, so I had set off to find out.

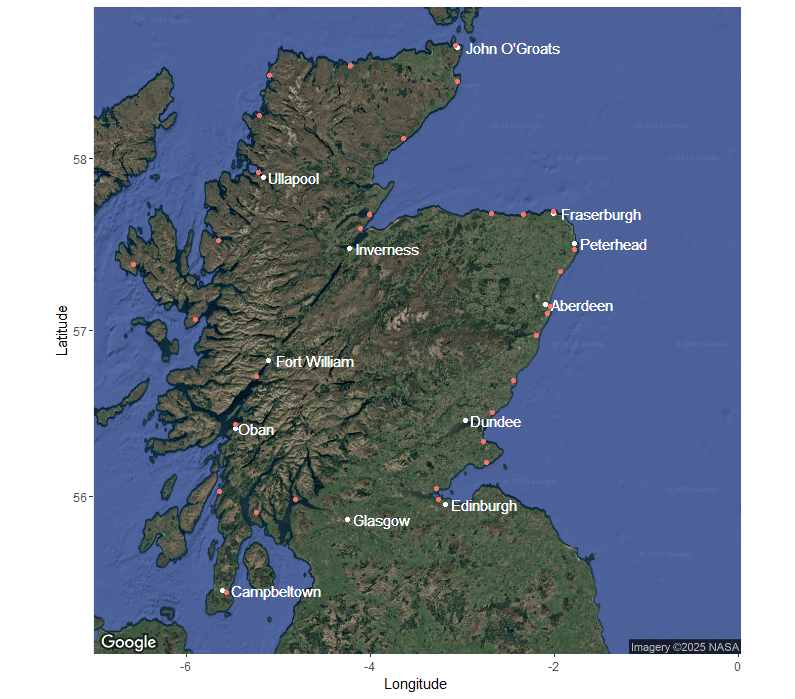

The route I had planned out started in Aberdeen, the granite bastion on Scotland’s north east coast, and went anti-clockwise around the coast of mainland Scotland, taking in the extremis of John O’Groats, the wild and windy shores of Kinlochbervie, two sites on the Isle of Skye (accessible with a bridge hence an easy one for me to do), right down to Campbeltown on the Kintyre peninsula (the whisky capital of the Victorian world), up past Glasgow and the grimy shores by Edinburgh, and along the sunny coast of Fife before arriving back in Aberdeen. In total I had lined up 35 sites from both pristine and (hopefully) more polluted areas, allowing me to study anemones who would differ in historic exposure to oil, diesel, and other hydrocarbon pollutants. My equipment may have been limited to some scalpels, syringes, vials, and plenty of ethanol, my transport may have sprung an ominous orange light, and my field assistant may have been a simple mutt unconcerned with the importance of data collection, but optimism flowed in my veins and with both the open seas and the winding road ahead of me I was excited to begin.

Wild camping by Gamrie was a magnificent first night on the road, with a breathtaking view down to the tiny fishing village of Crovie to accompany the first of my ready-made pasta diners and a mildly warm bottle of beer. I was wild camping for several reasons. Mostly as it was free, and hotels every night around some of Scotland’s most sought-after tourist spots would quickly drain the grant I had gratefully received from the Percy Sladen Memorial Fund. But wild camping also gives you great flexibility, got me close to the shore and the rock pools that I coveted, and was simply a wonderful opportunity to embrace the great outdoors. I did stay in hotels approximately every third night (I may or may not have smuggled the hound into the one in Inverness that was not pet friendly) to shower, charge my devices, and sterilise my scalpels in a sink (I may or may not have nearly set a towel alight in Campbeltown), but otherwise I was camping on beaches or grassy patches near the coast with the dog in the tent (except for the night when he rolled in a dead seal and had to endure a vigorous shampooing in Wick), cooking on my stove, washing in the sea, feeling the wind in my hair at all hours, and not wanting for much else.

It would be a bit of a fib if I said the work itself was exciting. I had identified sites based on iNaturalist records of the anemone, approximately evenly spaced them around the coast in an attempt to cover a range of conditions. Before arriving at a site, I whipped out OS maps on my phone to work out where the rocky shore should be in that area and so where to head to find rockpools and the little red gems within. I got pretty good at identifying suitable habitat this way and only occasionally had total busts and found nothing (the east shore of Loch Long still vexes me, and the less said about Dundee the better). Once I arrived, I leapt out the car, loaded my pockets and bum bag with my gear and notebook, and skipped down to sea. I wore shorts and crocs so I could splash around with impunity, and a padded gilet for the cold and the extra pockets. After the inevitable slight panic at finding nothing at first, typically I soon spotted a few tentacles waving at me from a suitable pool, and I breathe a sigh of relief and got to work. I squirted five anemones at each site with water from a syringe to record their “startle response” as a measure of behaviour, and with scalpels I sliced a small piece of tissue from ten individuals at each site to be preserved in ethanol and taken back to the lab for later genetic analysis. I was expecting anemones adapted to more polluted environments would be slower to re-extend their tentacles, as they interact with their environment through these tentacles and that is less worth doing if the environment is even slightly toxic. I did not yet know what genes in the tissue samples I expected to differ, but we had already performed an experiment in the laboratory (complete with white coats, bubbling jars, and maybe a small amount of cackling) which would give an idea of where to look once the arcane and mysterious bioinformatics was done. It was this ability to marry field work and laboratory studies that had drawn me to the beadlet anemone – many animals can be studied in the lab or the field, but not all that often both, and so this common Cnidarian offered a rare opportunity.

I have never lived so dependent on the tide and the weather. As I needed rockpools that were exposed, but full of water, I had to work while the tide was falling. This meant constantly checking the tide times and planning my day and driving around how many sites I could do for each tide. I was doing this during late June and early July, with incredibly long days, especially at the latitudes I was working at. Sunrise at John O’Groats on the 1st of July this year was at 04:08, while sunset was at 22:23. This meant that, if I was willing (and mostly I was), I could work well outside the 9 to 5, crouching over rockpools before 07:00 at Carsaig beach on the Kintyre peninsula and not finishing until nearly 22:00 at Armadale on the Isle of Skye. What it also meant was I had long spells, often in the middle of the day, where aside from driving to the next site, checking emails on my phone, and filing up with petrol (I did once pay an eye-watering £2.09 per litre), I had no great demands on my time. I dozed in the car to make up for missed sleep over night, tried coffee and cake at various coastal cafes, and took my canoe polo boat (a type of very manoeuvrable kayak used to play a sport with a ball and goals and little regard for personal safety) out for paddles to stay fit. Mostly I got lucky with the weather, it only really rained in Oban (as, I am reliably informed, it always does), and Campbeltown was pretty soggy (the whisky helps not mind that), but otherwise I applied suncream and donned a hat and stood or sat for minute after minute staring into blemish-less rockpools.

I drove for miles. Coasting along deserted coastal roads or creeping past tourists in camper vans at narrow passing places. I enjoy driving and that is a good thing as my schedule meant I often had to visit three sites in a day and possibly drive to be near the first site for the following day. This meant little dawdling, as if I finished a site and there was a still a couple of hours until low tide I climbed back into the car and rolled on to the next destination. Sometimes I regret this self-imposed pel-mel schedule; I could have sat on the dramatic Oldshoremore bay in Kinlochbervie for another day supping the remoteness, or explored Skye’s character, or any other of a thousand desirable things, but instead on I drove, lashed to my schedule, unable to deviate from the mindset of getting one site done and moving to the next as efficiently as possible. Ultimately it worked and I got done in 14 days with all my sites in the bag (minus a couple near Glasgow where anemones were not to be found but plus a replacement in Kilcreggan), but if it happens again maybe I would have the confidence to take my time here and there, sniff the breeze. I may or may not do this again but even if I don’t a student of mine hopefully will, building on and improving what I have made a clumsy first attempt at doing.

It’s 2025 and I am just back from paternity leave. Despite my excitement at gathering these samples completing priorities meant I never got round to extracting and analysing the DNA or understanding what was going on with the anemones’ startle response. However, in my first meeting with my PhD student Hamish he mentions that him and Abhiraj, a student I co-supervise, extracted DNA from all 355 samples. This is amazing as now the secrets of each individual anemone’s genetic code can be revealed to us and help us understand if they have evolved in response to exposure to pollution. I was thrilled by this development and cannot wait to take this project to the next stage. Plus, it’s nice to think back to those crazy two weeks when there was nothing much more than the sea, the sky, some rock pools, and a coastal road.