Lots of people track animals. Some do it to catch them for food, to detect when they might be near livestock, or more common among other biologists, to study them. Where an animal moves informs us about its foraging behaviour, if it has a territory and whether it overlaps with others, how active it is throughout the day and what type of terrain it uses. This has all sorts of uses for management, conservation and simply learning more about the natural world.

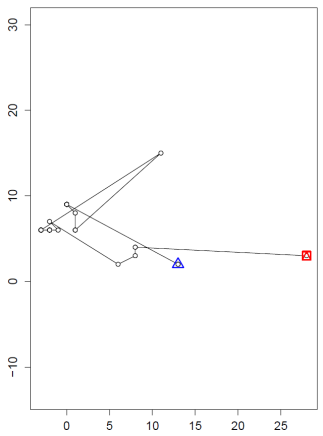

Tracks of 4 different carnivores

Tracks of 4 different carnivores

Whats got me thinking about this is a book, “The Wolverine Way”, by Douglas Chadwick. This is a recounting of his time spent helping to track wolverines in Montana. Very little is known about these elusive hunters and scavengers, yet what became abundantly clear from their tracks is that they were essentially super-charged roving machines. Covering incredible distances through winter, across seemingly inhospitable terrain and up intimidating peaks, it seems a wolverine never stops scouring the landscape

Also known as the masked glutton, Gulo gulo has a fearsome reputation amongst those who know them

Also known as the masked glutton, Gulo gulo has a fearsome reputation amongst those who know them

Another aspect that comes out of studying tracking data is the focus on the individual. Following the tracks of one particular animal over hills and round rivers and into crevices leads to a profound sense of connection with the animal; you picture their journey to share their endeavours and feel their exertions. This is something that has always come more easily to those studying large, charismatic animals such as dolphins, lions or even wolverines. Yet what happens when you track something small, uncharismatic and even a bit ugly?

Because that’s what I do, or at least, part of what I do. As mentioned in my bio I work on a project that uses video cameras to record the daily activities of a population of field crickets (Gryllus campestris). This gives us an unprecedented view into the lives of these individual crickets, as they search for mates, get attacked by predators and eventually die.

Crickets are observed by the cameras at the burrows they use to hide from predators. We record crickets moving among these burrows throughout their lifetimes. As we know the locations of these burrows, we are effectively tracking these crickets, albeit it more passively than if we had fitted tracking devices directly to individuals. On group does actually does this with honey bees, and have gained some amazing insights into how worker bees forage. The project I work on has produced plenty of reports of what our crickets get up to but we have not really looked into their movement. The closest we’ve coming is investigating what environmental variables influence how often they move around the meadow. But this totally ignores where they go.

This is where you, the interested reader, come in. I’m really hopeful that some people interested in movement ecology and animal tracking read this and have some ideas about how movement might differ among individuals and how it might differ between crickets and the kind of animals that normally get tracked. What we can also do is combine this information with what crickets do and what happens to them that might influence their movement. For example, do crickets go to ground after avoiding predation by a robin, or do they up sticks and get out of dodge city as fast as possible? This should give us a new angle entirely over what most other tacking studies can do, but at the moment that potential is totally unexplored.

In 2013 alone there were over 230 individuals, living an average of 24 days each and typically being sighted at multiple burrows over that time. I’m really convinced that this data is formidable, especially considering these crickets are around 2 cm long, weigh about a gram and hide the second a human walks within 5 metres. What they do with their time is largely a mystery.

Sadly I don’t have the time or expertise to get into this. But I‘m really up for discussing ideas, so drop me a line in the comments if you want to know more or have ideas!

How do you tell different crickets apart? Are there certain natural markings you look for, or are there just sensors detecting movement? The premise of the study sounds very interesting; I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that movement ecologists have generally neglected invertebrates, probably because of the logistical difficulties of tracking them like you describe. But keep at it, cause I can imagine a successful study would have incredibly interesting insights for insect ecology!

LikeLike

We glue little tags on their backs to recognise individuals, check out http://www.wildcrickets.org for some pictures.

Agree inverts have probably been neglected and we still have a lot to learn about them. What I hope would be that general insights abut movement ecology could be made alongside with findings abut insects in particular. But its not my field so I don’t really know!

LikeLiked by 1 person